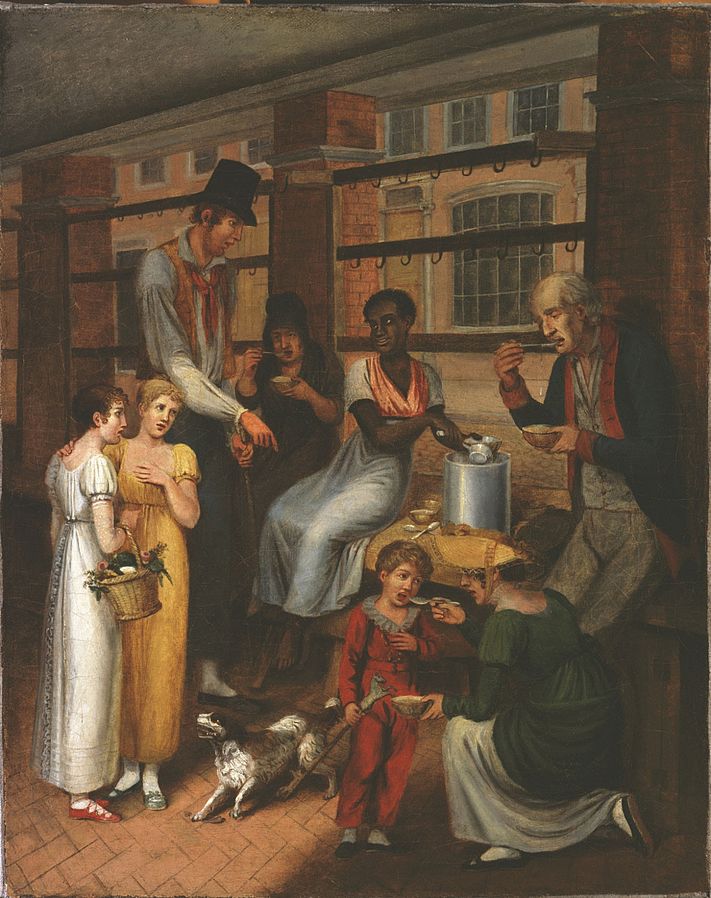

Pepper pot is one of many dishes from Philadelphia’s colonial past that is slowly being forgotten. Just like another famous Philadelphia dish that is becoming rarer to find, turtle soup, pepper pot demonstrates the love for spice and chillies that Philadelphians had during the colonial era.

Philadelphia pepper pot has a very well-known origin story. It’s said that during the American Revolution, in the winter of 1777-1778, George Washington and the Continental Army were holed up at Valley Forge, frigid and on the verge of starvation. General Washington had his chef throw together what ingredients they had on hand to make a stew to feed the soldiers. Having only tripe and vegetables available, the chef prepared a stew called pepperpot that nourished the troops and saved American Independence.

This story is most definitely a myth. Pepper pot, its precursors, and its variations come from the West Indies, as does the taste for highly-spiced stewed dishes. Caribbean immigrants sold pepper pot on the streets of colonial Philadelphia. Their cries proclaiming, “Pepper pot! All hot!” were a fixture of the city’s culture that predated the revolution.

Generally, Philadelphia pepper pot uses tripe, but there is no single definitive version of the dish. Pepper pot can really involve any meat and it’s changed again and again throughout the years.

I sourced multiple cookbooks from the colonial area to create my version of the dish, but it’s important to note that the Black Caribbean immigrants who actually invented pepper pot, didn’t write these cookbooks. It’s a sad fact that the foodways and household dishes of the racially oppressed and lower economic classes were rarely documented.

It should also be added that the Continental troops did truly starve at Valley Forge, but they were saved by the Oneida Nation. The Oneida allied with the revolutionaries during the war. They sent down sacks of their corn to support the soldiers and the matriarchs of the tribe taught the troops how to cook it — saving the soldiers’ lives and the war.

This story was told to me by Stephen Smith, Roughwood Seed Collection Manager, and Dr. William Woys Weaver, who grows and saves heirloom seeds, including the chillies I use in my version of pepper pot, buena mulatta and fish peppers. Roughwood also has the Oneida Nation maize.

If you’d like to learn more about this interesting history, buy seeds, or just help Roughwood with their cause, please visit their website.